The Forensic Science Geek of the Week

Please visit the www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com FaceBook fan page.

The week 64 “www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week” honors goes to: Richard L. Holcomb, Esquire.

Richard L. Holcomb, Esquire is our Geek of the Week

According to his website:

Richard L. Holcomb has been involved in Criminal Defense Practices since 2001. As reflected by his accomplishments, Mr. Holcomb has extraordinary experience as a criminal defense attorney. Mr. Holcomb has successfully litigated numerous Alcohol-related Cases. Mr. Holcomb has also served various roles in high-profile and nationally-publicized cases where the clients achieved remarkable results. Mr. Holcomb is also a dedicated family man. Mr. Holcomb’s wife is a local physical therapist. The Holcombs have a three-year-old son. They have extensive family in the Philippines with whom they maintain regular contact. Mr. Holcomb has served a variety of roles in defending citizens accused of participating in major crimes. Included among these cases are major federal drug conspiracies, murders, sex crimes, and cases involving important search and seizure issues. Many of these cases were “high profile” and several gained national media attention. Mr. Holcomb has been very dedicated to his clients and many defendants consistently achieved remarkable results. Mr. Holcomb has represented a number of clients on appeal. Mr. Holcomb was consistently hired by other lawyers to draft appellate briefs and otherwise assist in cases due to the product that Mr. Holcomb consistently produces. Defendants/Petitioners in those appeals have received extraordinary relief and have been saved years in prison. Mr. Holcomb gained widespread notoriety when he convinced Tennessee Courts that Tennessee’s “Crack Tax” was unconstitutional. This holding was affirmed by the Tennessee Supreme Court in a separate opinion and based on Mr. Holcomb’s briefing. Mr. Holcomb has also been invited to speak at several criminal defense lawyers’ seminars.

Congratulations to our Forensic Science Geek of the Week winner!

See the challenge question that our winner correctly answered.

OFFICIAL QUESTION:

- Forensic Science Geek of the Week Challenge

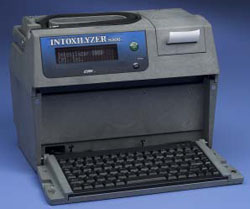

1. What is this called?

2. What technology is it based upon?

3. How does it work?

4. What are it’s limitations?

5. How is it scientifically calibrated?

Our Geek of the Week answered:

1. The Intoxilyzer 8000

2. Infrared Spectometry

3. Infrared light is shown through the sample chamber. Methyl-group molecules (and perhaps others) block certain frequencies of infrared light. A collector plate is at the other side of the sample chamber. Supposedly, infrared absorption is measured at both 3 and 9 microns. The light that actually made it through the chamber is compared with what was originally shone through. And, through a super-secret source code, algorithms are applied to convert the light measurement to a magic number which is then insisted is the testee’s BrAC.

4. It has a number of limitations including: a) it is non-exclusive (or imprecise) – a number of molecules will block the same frequency of light as does ethyl alcohol (interferents). The result is that alcohol is reported when the machine is actually measuring another chemical, that incidentally are frighteningly common (such as industrial chemicals, camphor, new car smell, and acetaldehyde -which is produced by diabetic’s lungs). b) It is highly susceptible to physiological variations in the test subject. For example, if the subject has GERD, the alcohol in the stomach can get into the mouth, contaminating the sample; hematocrit levels can falsely increase the result because the less liquid there is in the blood, the more concentrated the alcohol will “appear” to the machine; body and breath temperature can falsely elevate the result because of the machine’s misguided reliance on Henry’s Law – and, at least in Hawaii, the calibration-checkers assume that breath temperature is 34 degrees C, despite studies showing that the breath temp., on average, should be expected to rise to 35. Thus, the result is [perhaps] always overstated; c) breathing patterns (which the users cannot and do not attempt to control) can also effect the machine. Hyperventilating v. holding the breath can cause the result to report lower or higher; d) Lack of Sampling controls – the operators of the machine have no knowledge (at least in Hawaii) of the amount of air that is blown into the machine. In fact, as far as I know, Hawaii and all other states, instruct subjects to blow in and keep blowing as hard as they can for as long as they can. As Tom Workman’s studies in Fla and Mass show, the longer you breathe, the higher the result. Thus, instead of measuring 1.1 liters, as the machine supposedly can, the operators are trained to elevate the result (perhaps falsely) – and the other problem is that there can be no comparison because each subject would presumably blow a different volume of breath into the machine. e). The reason that they say they have subjects blow as hard as they can into the machine is because they are interested in “deep lung air.” Why? Ultimately, they believe that Henry’s law applies to the alveoli exchange – so the (incorrect) theory is that the harder you have someone blow, the more likely you will get air directly off the alveoli exchange, and Henry’s Law will apply to reveal how much alcohol is in the blood. The problem is that Henry’s law depends on a constant temperature and pressure, neither of which exists in the human lung, particularly when a person is blowing out as hard as they can. f). Studies show that different partition ratios should be applied to different subjects, yet most states – including Hawaii – have legislated a 1:2100 partition ratio, which results in inflated results (at least in many cases). g) The insides of the bronchial tubes contain moisture droplets, which also contain alcohol. How much alcohol, How many moisture droplets will be introduced into the measured sample, the density of those moisture droplets, etc. are all dependent upon the subject’s own personal physiology – which no man or machine could possibly account for – at least within the confines of a breath test. h). The uncertainty is not reported. Nothing is measured with 100% accuracy or precision. Yet, the probability that the number reported by the machine could actually be the BrAC is not estimated – except in WA and maybe MI. (In Hawaii they don’t even do duplicate testing, which means the result could be a statistical outlier); i) The means by which the machine generated the number is a closely guarded purported trade secret. Where other manufacturers permit defense lawyers to analyze the source code (the software that contains the algorithms and other data that operates the machine – and in this context, very importantly, allows the measurement of the infrared light and the conversion of that measurement to a magic number), analogous to peer-review which is necessary in science, CMI refuses to disclose the code, and literally, even CMI’s customers (the State) only believes the machine works because the guy who sold it to them says so; j) mouth alcohol – alcohol can linger in the mouth for a long period of time. 15 minute and 20 minute observation periods are often inadequate to ensure that all of the alcohol is out of the mouth. The machine has a “slope detector” which is supposed to detect mouth alcohol, but has been demonstrated to operate inconsistently, at best. This is famously shown in various seminars by having the subject eat Wonder Bread and use mouthwash. k) RFI – the machine is susceptible to radio frequency interference – such as using a cell phone. The use of an electronic device could result in an elevated result. Remarkably, CMI advertised the efficiency of the housing of the Intox 5000 as preventing RFI. However, with the 8000, they abandoned that housing in favor of portability. Now, they say that they have magic paint that blocks radio frequencies. Yet the machine remains susceptible to RFI and the error code for RFI does not always appear.

5. This question is a little bit difficult. We must routinely check calibration using a wet bath or dry gas simulator with a known sample. The wet bath simulator is what Hawaii uses. A liquid is heated in the simulator to 34 degrees C, it is agitated, and because of Henry’s Law, the vapor is blown through the 8000 and the results reported. If that is within an “acceptable” margin of error, it is deduced that the machine works “fine.” Your question appears to be what happens when the reading is outside the “acceptable margin of error.” Here, the answer is simple – nothing. What should happen is that the error should be calculated, again, using a known sample. Then, the manufacturer should either adjust the infrared light source (obviously replacing any defective part, whether it be the source, the sample chamber, collector plate, etc.) or, if the error of the machine can be demonstrated as some mathematically comprehensible error (it is off by x% in every test), then I suppose the software (calculations) could be adjusted to give an acceptable result. Obviously, the machine should be tested and it ensured it is reporting acceptable results thereafter.

[BLOGGER’S NOTE: What a great answer. That is what this blog is all about. Thank you for participating. Congratulations on being our Geek of the Week.]

The Hall of Fame for the www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week:

Week 1: Chuck Ramsay, Esquire

Week 2: Rick McIndoe, PhD

Week 3: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 4: Stephen Daniels

Week 5: Stephen Daniels

Week 6: Richard Middlebrook, Esquire

Week 7: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 8: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 9: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 10: Kelly Case, Esquire and Michael Dye, Esquire

Week 11: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 12: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 13: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 14: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 15: Joshua Dale, Esquire and Steven W. Hernandez, Esquire

Week 16: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 17: Joshua Dale, Esquire

Week 18: Glen Neeley, Esquire

Week 19: Amanda Bynum, Esquire

Week 20: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 21: Glen Neeley, Esquire

Week 22: Stephen Daniels

Week 23: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 24: Bobby Spinks

Week 25: Jon Woolsey, Esquire

Week 26: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 27: Richard Middlebrook, Esquire

Week 28:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 29: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 30: C. Jeffrey Sifers, Esquire

Week 31: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 32: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 33: Andy Johnston

Week 34: Ralph R. Ristenbatt, III

Week 35: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 36: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 37: Jeffrey Benson

Week 38: Pam King, Esquire

Week 39: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 40: Robert Lantz, Ph.D.

WEEK 41: UNCLAIMED, IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 42: Steven W. Hernandez, Esquire

Week 43:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 44: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 45: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 46:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 47:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 47:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 48: Leslie M. Sammis, Esquire

Week 49: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 50: Jeffery Benson

Week 51: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 52: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 53: Eric Ganci, Esquire

Week 54: Charles Sifers, Esquire and Tim Huey, Esquire

Week 55: Joshua Andor, Esquire

Week 56: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 57: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 58: Eric Ganci, Esquire

Week 59: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 60: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 61: UNCLAIMED IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 62: UNCLAIMED IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 63: Ginger Moss

Week 64: Richard L. Holcomb, Esquire