At this blog we have been following the great reporting of The Boston Globe over the Annie Dookhan matter. This is a very important case study of what can go wrong and what does go wrong in forensic science. I have called it before the Fukushima of Forensics. This is not hyperbole. As you read more and more about this scandal, we are only beginning to appreciate how deep the rabbit hole is.

- Yet another crime lab scandal — the real question is how many failures until they get caught and when is enough enough?

- The poster child for everything that is wrong in forensic science: Annie Dookhan

- The Fukushima of Forensics: Annie Dookhan

- What to do with 60,000 cases involving Annie Dookhan?

How a chemist circumvented her lab’s safeguards

Close supervision is key in a lab, specialists say, and Annie Dookhan’s appeared to lack it

By Kay Lazar | GLOBE STAFF

SEPTEMBER 30, 2012

State drug lab chemist Annie Dookhan labeled the vials as containing THC, the active ingredient in marijuana. But when another chemist ran the vials through a machine to confirm Dookhan’s analysis, one had little THC, and another was mixed with morphine and codeine.

The second chemist sent the vials back to Dookhan to resolve the discrepancies, asking her to repeat the screening test the lab used to tentatively identify the drugs in an evidence bag. When she resubmitted them, the machine showed the vials contained pure THC.

The incident, detailed in a 100-page State Police report obtained by the Globe last week, illustrates one of the many ways Dookhan was able to circumvent safeguards intended to ensure that drug evidence was properly handled and analyzed by workers in a now-closed lab formerly run by the state Department of Public Health.

Forensics specialists interviewed by the Globe say the lab’s procedures appear to have been fairly standard, including having two chemists test every sample, but they were still not enough to prevent an ambitious chemist’s rampant breaches of lab protocol, apparently to boost her performance record. In the process, investigators say, Dookhan has jeopardized the reliability of drug evidence used in 34,000 cases during her nine-year career.

The 34-year-old chemist was arrested Friday and charged with two counts of obstruction of justice and one of falsifying her academic record, in allegedly lying under oath about having a master’s degree in chemistry.

Dookhan was “dry-labbing” her screening tests. Put simply, she was skipping a critical first step, according to her admission to investigators, and instead often made a preliminary identification of drugs simply by how they looked and by the type of suspected drug that was checked off on a control card that accompanied the sample.

Typical lab protocols require an initial screening test, called a color test, in which a chemist applies a specific liquid to each drug sample to determine its identity by the color it turns.

That result is crucial for properly performing a second, more definitive test. It tells the chemist doing that second test what “control” drug to use to compare with the sample being analyzed.

“Dry-labbing is probably the most sinful thing that a chemist can do because it is essentially cheating,” said Thomas E. Workman, a criminal defense lawyer who teaches courses on scientific evidence at the University of Massachusetts Law School.

Workman would like to see cameras added to crime labs to record screening tests, with footage available on the Internet to prosecutors and defense lawyers to help ensure that proper procedures are followed.

Use of cameras is not standard practice in crime labs, said Ralph Keaton, executive director of the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board, an agency that certifies hundreds of crime labs nationally, including those run by Massachusetts State Police.

Instead, well-run labs use quality managers who check daily to ensure that staff members have properly calibrated machines and that protocols are being followed, said Ralph Timperi, who stepped down in April 2005 after 18 years as director of the Jamaica Plain state lab complex, which included the drug testing lab.

“There are different kinds of checks and balances, and a supervisory one is critical,” Timperi said. “You need someone walking around and observing what people are doing and looking for problems.”

It is not clear whether the drug lab continued to use quality managers after Timperi’s departure. Alec Loftus, a Patrick administration spokesman, declined a request for a copy of the lab’s policy and procedures manual, saying it was protected as part of the criminal investigation of the lab by State Police and Attorney General Martha Coakley.

But the State Police report suggests Dookhan herself may have, at times, served in another quality assurance role, as the lab’s quality control chemist, who typically runs daily tests to ensure scales are calibrated and machines are running properly.

“These machines could have been used by other chemists, who did not even know that the machines were not properly verified,” said Workman.

That possibility, Workman said, would call into question a much larger universe of drug tests beyond the 60,000 Dookhan is believed to have run during her tenure.

Investigators have already identified 1,141 inmates of state prisons and county jails who were convicted based on evidence analyzed by Dookhan. And judges have freed, reduced bail for, or suspended the sentences of at least 20 drug defendants in the scandal.

Dookhan allegedly removed evidence from the lab’s secure area without authorization, forged colleagues’ initials on control sheets that record test outcomes, and intentionally contaminated samples to make them test positive, after they were sent back to her to re-check because she had “dry-labbed” instead of completing the required preliminary tests.

While colleagues were suspicious of her shoddy work habits and unusually high output and reported concerns to supervisors, little action was taken for more than a year, according to the police inquiry.

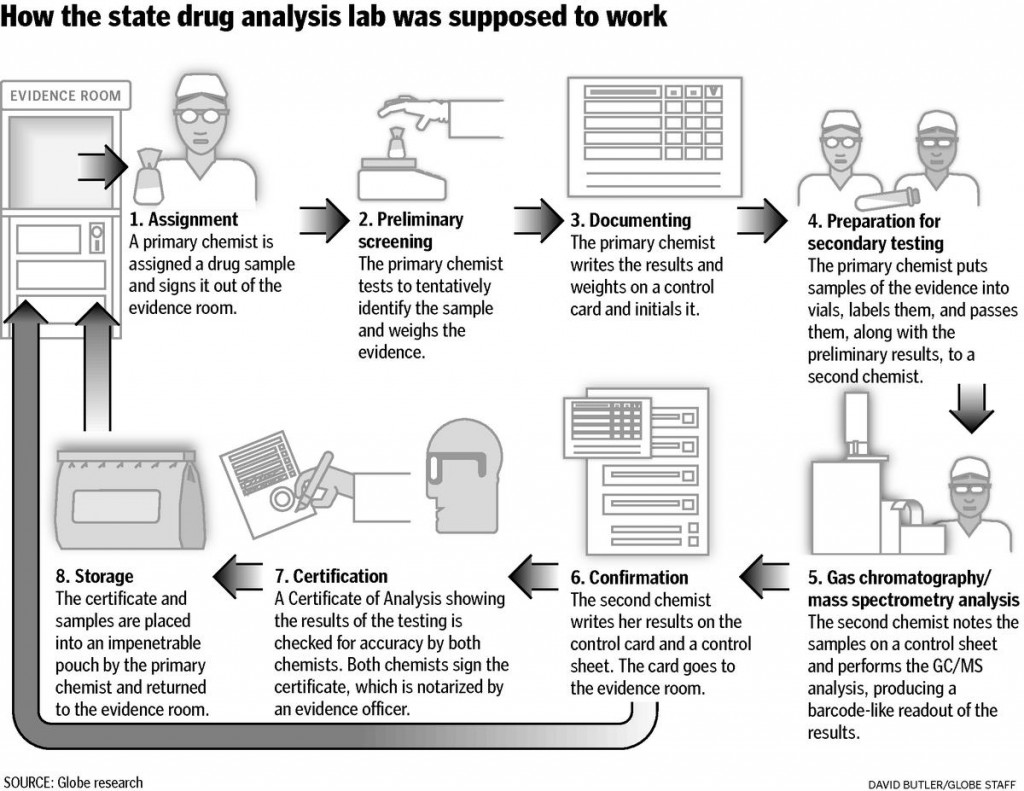

A one-page overview of the lab’s routine procedures, provided to the Globe from someone familiar with its operations before it was closed in August, indicates that a primary chemist is assigned a sample from the lab’s evidence room, weighs it, and performs testing to preliminarily identify it. That person then prepares vials of the substance to send to a secondary chemist, known as the lab’s GC/MS person, who analyzes the vials in a machine to confirm the identification.

That process, known as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, first separates drug samples into their component parts. For instance, it separates cocaine from the baking powder, laxatives, or other substances drug dealers typically cut the drug with to inflate its weight. Next, the machine analyzes the chemicals and prints out a characteristic pattern, similar to a bar code, that is used to identify a sample. For instance, it compares the pattern for the sample of presumed cocaine being tested to the pattern of a known sample of cocaine.

The GC/MS chemist analyzes the printout and records the results on a control sheet, which is initialed by that chemist and the primary chemist on the case, and then the primary chemist returns the original samples and all documentation to an evidence officer.

“The GC/MS [machine] produces a printed, recorded analysis of the sample, but unless you are highly trained you may not be able to know if it’s traceable to a specific sample of evidence,” said Justin McShane, a Pennsylvania criminal defense attorney and senior instructor in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry at the American Chemical Society, a trade group of more than 164,000 chemists.

Because of the complexity, and lack of cameras recording the preliminary tests, McShane said, it is possible for an unscrupulous chemist to dupe colleagues and prosecutors and defense lawyers, who depend on the work but are rarely given more than a simple card that indicates whether the evidence was positive or negative for illicit drugs.

McShane said he routinely hears “horror stories” from chemists he trains about unrelenting pressure to test more samples. Dookhan allegedly confessed to State Police that she forged colleagues’ initials and contaminated samples to “get more work done,” according to their report.

“You are judged by numbers in the lab,” McShane said. “There is a culture of pressure to get it done with no new resources. But there is no excuse for [cheating] at the end of the day.”