I defy anyone to logically put forth an argument that it is ever “ok” in our modern world to allow someone who is objectively innocent spend one minute in jail. If you exist, then we would really like to hear from you.

Incredibly, all across the United States and even in our federal court system, arbitrary procedural time restrictions promote and create exactly that. Innocence foreclosed. Justice denied. That is wrong.

In fact, SCOTUS justice Antonin Scalia once famously penned “This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is ‘actually’ innocent.” (from the Troy Davis death penalty case). Just last year, the SCOTUS reversed the 9th Circuit case of Shirley Ree Smith wherein modern kinetics and modern science was used to examine a Shaken Baby Syndrome case (SBS) and falsify the science presented at trial. Modern science didn’t matter to the majority. The The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 did.

According to a blog at hypervocal,

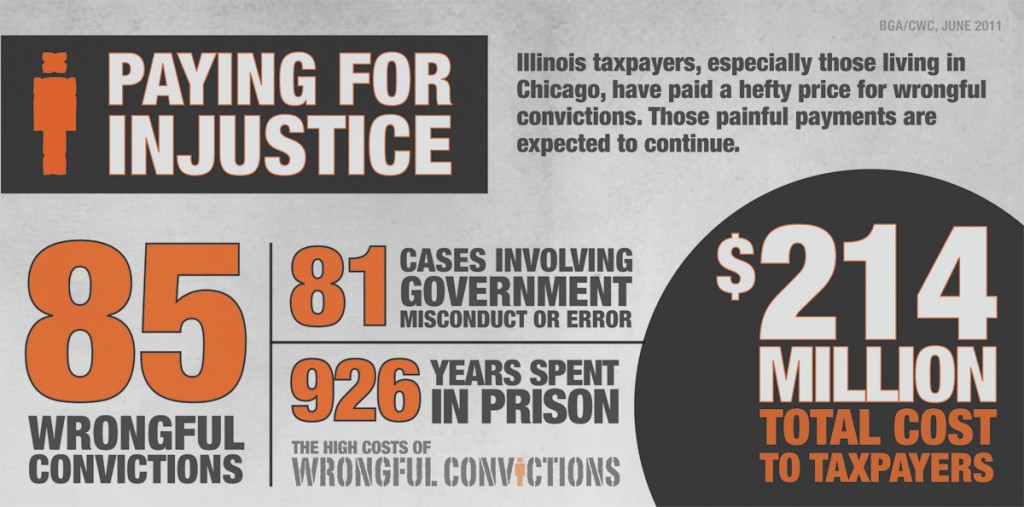

[In 2011, after a] stunning seven-month investigation by the Better Government Association and the Center on Wrongful Convictions shows that “wrongful convictions of men and women for violent crimes in Illinois have cost taxpayers $214 million and have imprisoned innocent people for 926 years.”

Yup, nearly a millennium of hard time for innocent people.

Here’s the kicker: The report tracked exonerations from 1989 through 2010 and concluded that while “85 people were wrongfully incarcerated, the actual perpetrators were on a collective crime spree that included 14 murders, 11 sexual assaults, 10 kidnappings and at least 59 other felonies.”

Remember this is just one state!

A Texas Bill may be changing all of this and promoting the truth.

Bill Addresses Changing Science in Criminal Appeals

by Maurice Chammah of the Texas Tribune

Advocates are backing a renewed push to streamline the appeals process for those who were convicted based on science that has since been discredited.

Senate Bill 344, filed Monday by state Sen.John Whitmire, D-Houston, would establish a statute expressly allowing Texas courts to overturn convictions in cases where the forensic science that originally led to the verdict has changed. State Rep. Sylvester Turner, D-Houston, filed a companion bill,HB 967, on Tuesday.

Though the proposal has failed twice before, Whitmire said that several recent Court of Criminal Appeals decisions may make it more likely to pass, and that prosecutors who have opposed it in the past should come around. “Why wouldn’t we want to find out there’s flawed evidence based on new science?” he said.

Currently, people convicted of a crime in Texas can submit a writ of habeas corpus to the Court of Criminal Appeals, in which they ask for a new trial based on evidence that was not available when they were originally convicted. If the science used to convict them has changed, there is no special guideline allowing the court to grant them a new trial, and the judges often disagree about whether to do so.

Supporters of the bill point to the history of DNA testing as an example for why the change is needed. In 1998, the Court of Criminal Appeals denied a new trial to Roy Criner, then serving 99 years for a rape and murder, even though new DNA evidence suggested that Criner was innocent. Then-Gov. George W. Bush pardoned Criner in 2000, and in 2001, the Legislature created Chapter 64 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which streamlined the process for new testing of DNA.

The laws surrounding writs of habeas corpus are designed to keep those convicted from filing lots of appeals that are frivolous. “Habeas law creates a lot of problems for defense,” said Sandra Thompson, director of the Criminal Justice Institute at the University of Houston Law Center. “It was designed to keep from there being too many bites at the apple. We’re trying to loosen up these procedures in cases where there might be a false conviction.”

Prosecutors from Harris County who have previously opposed the bill didn’t immediately return a request for comment on the bill, but in the past some prosecutors have said similar bills were unnecessary because the system for filing appeals is already “well established.”

The proposal has long been supported by the Innocence Project of Texas. “I think some legislation establishing black and white procedures, and a concrete process with articulated standards of review would assist both defendants and the state,” said Mike Ware, an attorney with the organization, “in knowing what has to be done in order to obtain the desired relief.”

This is not the first time Whitmire has tried to pass a bill to account for changing forensic science. In 2009, a nearly identical bill passed through the Senate, only to get pushed off the House floor agenda during the voter ID fight.

The reform was one of many laid out by the 2010 Timothy Cole Advisory Panel on Wrongful Convictions, which made policy recommendations based on its review of overturned convictions.

In 2011, bills in the House and Senate were filed but not rigorously pursued because lawmakers focused more on reforming eyewitness identification practices.

But since the last legislative session, a handful of opinions from the Court of Criminal Appeals have led some advocates to argue that this session might be different.

In February 2012, Court of Criminal Appeals Judge Cathy Cochran wrote an order for a hearing on the appeal of Hannah Overton, who was convicted of poisoning her foster son in 2007 with salt. Doctors testifying for the defense later found it was more likely that the foster son had overdosed on the salt himself.

“This disconnect between changing science and reliable verdicts that can stand the test of time has grown in recent years,” Cochran wrote, “as the speed with which new science and revised scientific methodologies debunk what had formerly been thought of as reliable forensic science has increased.” The Court of Criminal Appeals has not yet decided whether Overton is entitled to a new trial, though the state district judge who oversaw the hearing said that the new scientific evidence would not have changed the trial’s result.

In December, the CCA ordered a new trial for death row inmate Cathy Lynn Henderson, who had been convicted in 1994 for beating to death a child she had been baby-sitting. “Changing science has cast doubt on the accuracy of the original jury verdict,” Judge Cochran explained. Travis County District Judge Jon Wisser, who had overseen the trial, found that the jury would not have convicted Henderson if they had been aware of discoveries made since regarding head trauma. New studies showing that falls of less than 4 feet could be lethal, potentially corroborating Henderson’s claims that the victim had fallen accidentally. The medical examiner who originally completed the autopsy and testified against Henderson, saying it would have been “impossible” that the victim had fallen, had since revised his position and said the child could have fallen.

The court’s order in the Henderson case was accompanied by three concurring opinions and two dissenting opinions. “Something is missing here,” Judge Barbara Hervey wrote in her dissent. “To justify its decision, the Court makes a quantum leap from ‘advances in science’ to granting relief, which presents a whole new dilemma for the criminal justice system and this case in particular.” Judge Michael Keasler said in a dissent he was “baffled and appalled” by the decision.

Ware said the Henderson case shows that a statute like the one Whitmire is proposing needs to be passed so that there is not this sort of disagreement in the future. He is preparing to file a writ in the case of four San Antonio women convicted largely on medical findings of sexual assault that have since been questioned as pediatric gynecologists have revised their methods for ascertaining whether an assault took place.

Roe Wilson, an assistant district attorney with Harris County who for 20 years served as bureau chief for post-conviction writs, said the proposed bill is “unnecessary because newly discovered evidence, including scientific evidence, can be presented in a subsequent writ application.”

“The bill’s language concerning contested scientific evidence is overbroad,” she added, “as opposing experts can be found for nearly all expert testimony and evidence.”

A House Research Organization analysis of a similar bill in 2009 noted that some prosecutors saw the bill as “unnecessary,” because “the current system for filing and considering writs of habeas corpus is well established.” The opposition recommended that instead convicted people might be allowed to submit motions to the court requesting new forensic testing, as is currently done with DNA.

Supporters of the bill also point to the Innocence Project’s ongoing arson review, which involves studying more than 1,000 cases for potential wrongful convictions based on flawed fire science. Nick Vilbas, who directs the project, said that roughly six to eight cases will probably be presented to the state fire marshal’s office, and some of the defendants in those cases will probably appeal their sentences based on the findings.

This bill, Vilbas said, will create a clearer guideline for judges reviewing these appeals. “The state of Texas has made historical steps with arson science. We’re going to lead the nation,” he explained. “It would be an injustice to get through all of that and find we can’t get relief for these guys simply because a standard has not been defined. It just needs to be clear”