I was at the 247th American Chemical Society meeting in Dallas where this research was first presented. Analytical instruments are destined to become more sensitive, it is the march of progress.

But is this a good thing?

Just because we can detect something, is it relevant?

Is examining toxicological samples at 1000 times more sensitivity really helpful to determine the issue or is it really superfluous sensitivity?

What does massively increasing sensitivity do to the assay’s specificity?

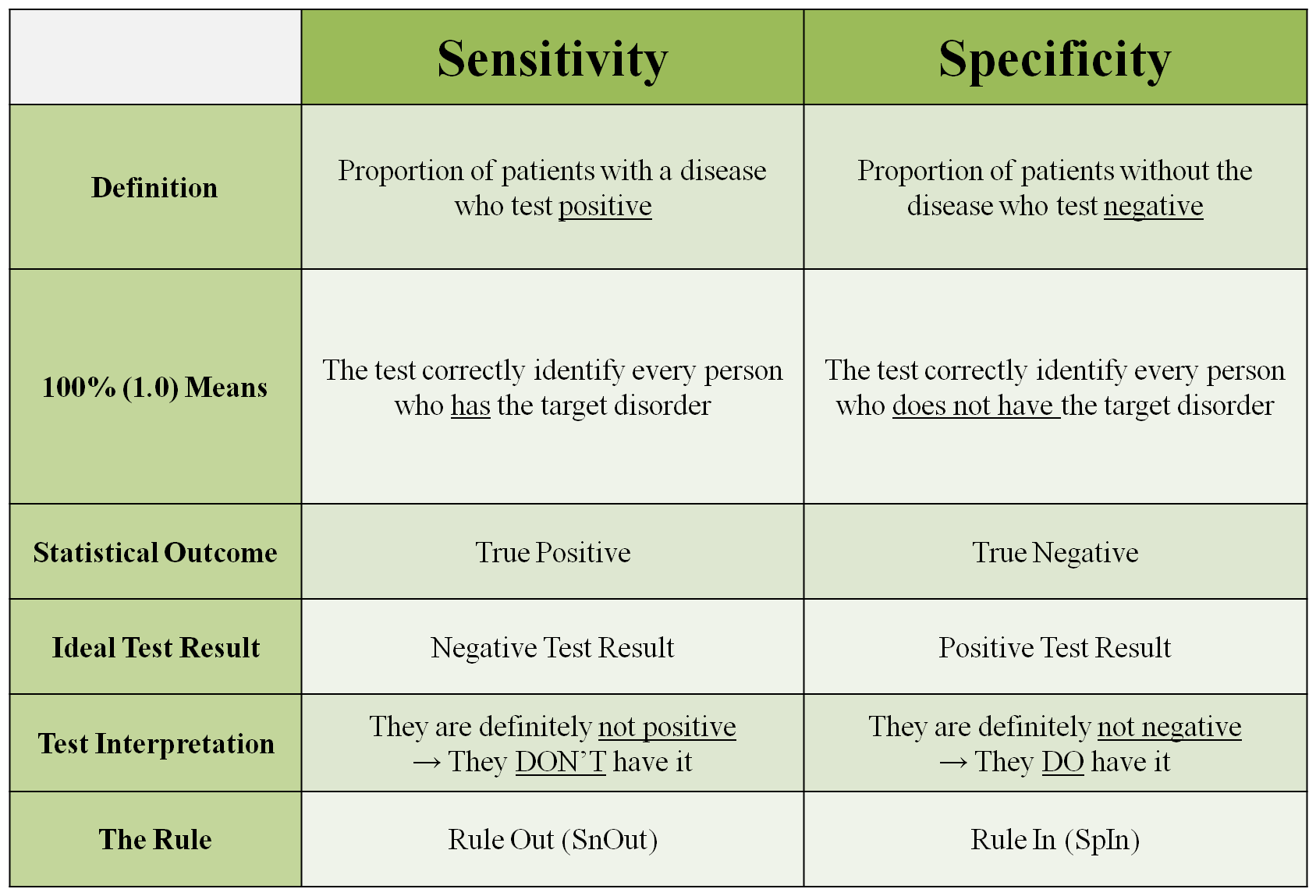

Sensitivity is just one of many metrics that should be used to determine relevance of a test result.

Think of a metal detector.

It is highly sensitive. It will go off 99.9% of the time for guns. It is not at all specific. When it goes off, it will go off for a whole bunch of things. It is very, very sensitive. It will get a normal man’s belt buckle. It is not at all specific to guns. I cannot think of a time where it has gone off in my presence when it has been a gun. In fact, every time I have heard it or seen it go off, it is a false positive for something that is not a gun. Does it make sense to make a metal detector 1000 times more sensitive?

This is the difference between analytical sensitivity and analytical specificity as summarized below.

New method is a thousand times more sensitive to performance-enhancing drugs

Date:March 18, 2014Source:American Chemical SocietySummary:

While the world’s best athletes competed during last month’s winter Olympics, doctors and scientists were waging a different battle behind the scenes to make sure no one had an unfair advantage from banned performance-enhancing drugs. Researchers have now unveiled a new weapon — a test for doping compounds that is a thousand times more sensitive than those used today.

While the world’s best athletes competed during last month’s winter Olympics, doctors and scientists were waging a different battle behind the scenes to make sure no one had an unfair advantage from banned performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs). Now, for the first time, researchers have unveiled a new weapon — a test for doping compounds that is a thousand times more sensitive than those used today.

The team described the approach at the 247th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society, taking place in Dallas through Thursday.

“How much of a drug someone took or how long ago they took it are beyond the analyst’s control. The only thing you can control is how sensitive your method is,” said Daniel Armstrong, Ph.D., who led the team. “Our goal is to develop ultra-sensitive methods that will extend the window of detection, and we have maybe the most sensitive method in the world.”

Hongyue Guo, a graduate student in Armstrong’s lab at the University of Texas at Arlington, explained that the new strategy is a simple variation on a common testing technique called mass spectrometry (MS). The International Olympic Committee, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency and others routinely use MS to ensure athletes are “clean.” MS separates compounds by mass, or weight, allowing scientists to determine the component parts of a mixture. In the case of PEDs, technicians use the method to find the bits left over in blood, urine or other body fluids after the body breaks the dopants down.

Because some of the pieces, or metabolites, are small and have a negative charge, they may not produce a signal strong enough for the instrument to detect, Armstrong explained — — especially in the case of stimulants, which the body rapidly breaks down. Stimulants like amphetamine, or “speed,” increase alertness and reduce an athlete’s sense of fatigue.

The method Armstrong’s lab has pioneered, called paired ion electrospray ionization (PIESI, pronounced “PIE-zee”), gathers several of those drug bits together, making them more obvious to the detector.

So far, Guo has used PIESI to detect different kinds of steroids and stimulants, as well as alcohol. That last one might not seem a likely choice for athletes looking to get an edge, but Armstrong explained that in shooting sports, alcohol and other depressants can help steady small muscle movements. Guo has demonstrated that the technique is often sensitive enough to detect one part per billion of the PED metabolite in urine, which he said is up to 1,000 times better than existing methods.

Testing laboratories wouldn’t need to purchase new equipment to get PIESI’s advantages, according to Guo. The new method only requires adding one ingredient to existing MS procedures, and Guo noted that the chemical is already commercially available and inexpensive. Today is the first time anyone has reported using PIESI on banned dopants, but Armstrong said now that the information is out there, he expects anti-doping agencies to quickly get on board.

“PIESI is going to be useful in so many different areas,” Armstrong said. Already, it’s being used to detect compounds crucial to human health such as phospholipids and pesticides and herbicides, as well as other environmental pollutants. In some cases, he noted, PIESI is 100,000 times more sensitive than other detection methods.

The research was funded by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Y 0026).