The pharmacology of ethanol has been well-studied for a great many years. Lost to antiquity is precisely where and when the pharmacodynamics of ethanol was first studied. However, it is clear that ethanol’s effects on the human being was well known dating back to perhaps neolithic times perhaps as long ago as 9,000 years ago.

The modern formal medicinal study of pharmacology and ethanol pharmacokinetics dates back to mid-19th century. Our formal understanding of the pharmacokinetics of ethanol became well-settled shortly thereafter. It was understood that the elimination of ethanol through oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver from the human body is rate-limited. This gave rise to the easiest model of pharmacokinetics (that of ethanol) known as the zero-order kinetic model, which means that the time-course of elimination generally follows a steady and predictable rate. This was good old-fashioned observation based experimentation. It was shortly thereafter discovered that ethanol binds to acetylcholine, GABA, serotonin, and NMDA receptors to produce its pharmacodynamic effects.

Without a doubt ethanol is the most well studied drug in the history of mankind.

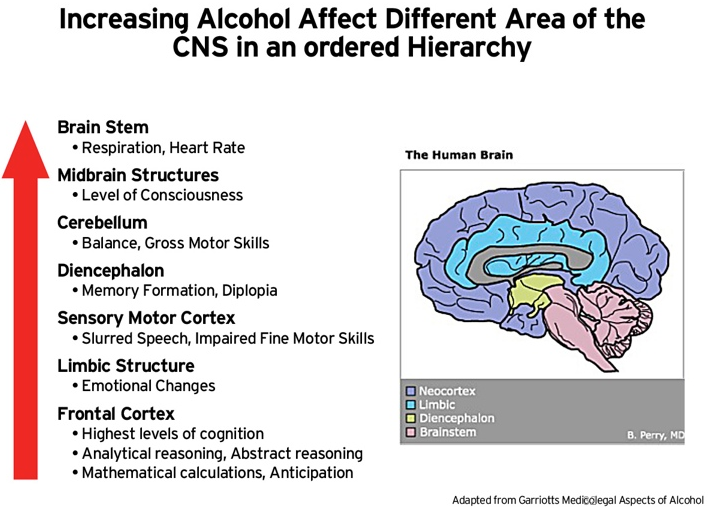

As such, the scientific community has settled upon its expected mechanism of action in terms of its effects generally and in relation to a specific BAC level. There is a hierarchical relation whereby the effect of ethanol begins in the more complex areas of the brain and terminating in the basic survival-related function and that the order of effect increases based upon BAC. It is a hierarchical relationship that settled observations at certain BAC levels would appear in the person additively and not randomly. In other words, effects noted to be present at a 0.16-0.20 would necessarily have features of the previous stages In other words, if gross motor function was impaired (which happens at higher concentrations), but abstract reasoning or executive decision making functions were intact (which happens at relatively lower concentrations), then according to the generally accepted and well-studied pharmacological effects of ethanol, the noted gross motor dysfunction could not be due to ethanol.